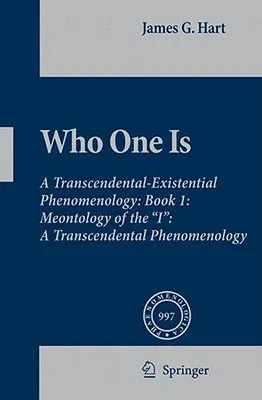

Both volumes of this work have as their central concern to sort out

who one is from what one is. In this Book 1, the focus is on

transcendental-phenomenological ontology. When we refer to ourselves we

refer both non-ascriptively in regard to non-propertied as well as

ascriptively in regard to propertied aspects of ourselves. The latter is

the richness of our personal being; the former is the essentially

elusive central concern of this Book 1: I can be aware of myself and

refer to myself without it being necessary to think of any

third-personal characteristic; indeed one may be aware of oneself

without having to be aware of anything except oneself. This

consideration opens the door to basic issues in phenomenological

ontology, such as identity, individuation, and substance. In our

knowledge and love of Others we find symmetry with the first-person

self-knowledge, both in its non-ascriptive forms as well as in its

property-ascribing forms. Love properly has for its referent the Other

as present through but beyond her properties.

Transcendental-phenomenological reflections move us to consider

paradoxes of the "transcendental person". For example, we contend with

the unpresentability in the transcendental first-person of our beginning

or ending and the undeniable evidence for the beginning and ending of

persons in our third-person experience. The basic distinction between

oneself as non-sortal and as a person pervaded by properties serves as a

hinge for reflecting on "the afterlife". This

transcendental-phenomenological ontology of necessity deals with some

themes of the philosophy of religion.