Donna Kornhaber

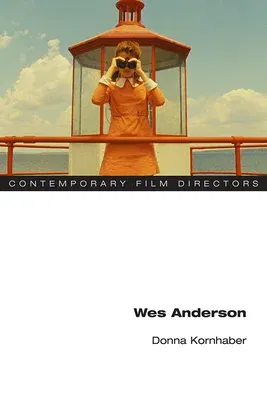

(Author)Wes AndersonPaperback, 16 August 2017

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

Only 2 left

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Contemporary Film Directors

Part of Series

Contemporary Film Directors (Paperback)

Print Length

194 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of Illinois Press

Date Published

16 Aug 2017

ISBN-10

0252082729

ISBN-13

9780252082726

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

16 August 2017

Dimensions:

20.83 x

13.97 x

1.52 cm

ISBN-10:

0252082729

ISBN-13:

9780252082726

Language:

English

Pages:

194

Publisher:

Weight:

272.16 gm