In this original and engaging work, author Kent Puckett looks at how

British filmmakers imagined, saw, and sought to represent its war during

wartime through film. The Second World War posed unique representational

challenges to Britain's filmmakers. Because of its logistical enormity,

the unprecedented scope of its destruction, its conceptual status as

total, and the way it affected everyday life through aerial bombing,

blackouts, rationing, and the demands of total mobilization, World War

II created new, critical opportunities for cinematic representation.

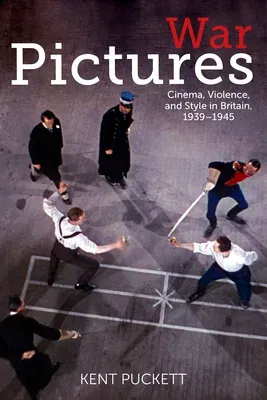

Beginning with a close and critical analysis of Britain's cultural

scene, War Pictures examines where the historiography of war, the

philosophy of violence, and aesthetics come together. Focusing on three

films made in Britain during the second half of the Second World

War--Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of

Colonel Blimp (1943), Lawrence Olivier's Henry V (1944), and David

Lean's Brief Encounter (1945)--Puckett treats these movies as objects of

considerable historical interest but also as works that exploit the full

resources of cinematic technique to engage with the idea, experience,

and political complexity of war. By examining how cinema functioned as

propaganda, criticism, and a form of self-analysis, War Pictures reveals

how British filmmakers, writers, critics, and politicians understood the

nature and consequence of total war as it related to ideas about freedom

and security, national character, and the daunting persistence of human

violence. While Powell and Pressburger, Olivier, and Lean developed

deeply self-conscious wartime films, their specific and strategic use of

cinematic eccentricity was an aesthetic response to broader

contradictions that characterized the homefront in Britain between 1939

and 1945. This stylistic eccentricity shaped British thinking about war,

violence, and commitment as well as both an answer to and an expression

of a more general violence.

Although War Pictures focuses on a particularly intense moment in time,

Puckett uses that particularity to make a larger argument about the

pressure that war puts on aesthetic representation, past and present.

Through cinema, Britain grappled with the paradoxical notion that, in

order to preserve its character, it had not only to fight and to win but

also to abandon exactly those old decencies, those "sporting-club

rules," that it sought also to protect.