How epidemic photography during a global pandemic of bubonic plague

contributed to the development of modern epidemiology and our concept of

the "pandemic."

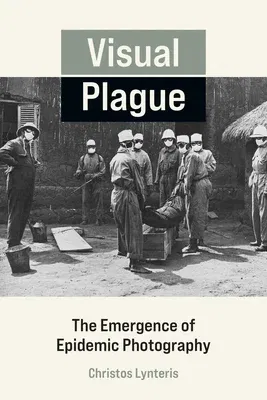

In Visual Plague, Christos Lynteris examines the emergence of epidemic

photography during the third plague pandemic (1894-1959), a global

pandemic of bubonic plague that led to over twelve million deaths.

Unlike medical photography, epidemic photography was not exclusively, or

even primarily, concerned with exposing the patient's body or medical

examinations and operations. Instead, it played a key role in

reconceptualizing infectious diseases by visualizing the "pandemic" as a

new concept and structure of experience--one that frames and responds to

the smallest local outbreak of an infectious disease as an event of

global importance and consequence.

As the third plague pandemic struck more and more countries, the

international circulation of plague photographs in the press generated

an unprecedented spectacle of imminent global threat. Nothing

contributed to this sense of global interconnectedness, anticipation,

and fear more than photography. Exploring the impact of epidemic

photography at the time of its emergence, Lynteris highlights its

entanglement with colonial politics, epistemologies, and aesthetics, as

well as with major shifts in epidemiological thinking and public health

practice. He explores the characteristics, uses, and impact of epidemic

photography and how it differs from the general corpus of medical

photography. The new photography was used not simply to visualize or

illustrate a pandemic, but to articulate, respond to, and unsettle key

questions of epidemiology and epidemic control, as well as to foster the

notion of the "pandemic," which continues to affect our lives today.