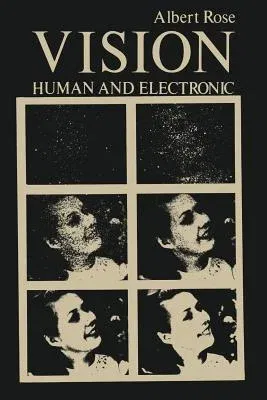

Albert Rose

(Author)Vision: Human and Electronic (Softcover Reprint of the Original 1st 1973)Paperback - Softcover Reprint of the Original 1st 1973, 25 November 2012

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Optical Physics and Engineering

Print Length

197 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Springer

Date Published

25 Nov 2012

ISBN-10

1468420399

ISBN-13

9781468420395

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Edition:

Softcover Reprint of the Original 1st 1973

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

NL

Date Published:

25 November 2012

Dimensions:

22.86 x

15.24 x

1.17 cm

ISBN-10:

1468420399

ISBN-13:

9781468420395

Language:

English

Location:

New York, NY

Pages:

197

Publisher:

Weight:

299.37 gm