In Moby-Dick, Ishmael declares, "Be it known that, waiving all

argument, I take the good old fashioned ground that a whale is a fish,

and call upon holy Jonah to back me." Few readers today know just how

much argument Ishmael is waiving aside. In fact, Melville's antihero

here takes sides in one of the great controversies of the early

nineteenth century--one that ultimately had to be resolved in the courts

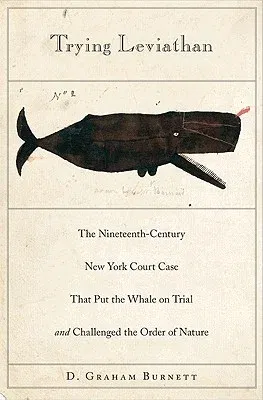

of New York City. In Trying Leviathan, D. Graham Burnett recovers the

strange story of Maurice v. Judd, an 1818 trial that pitted the new

sciences of taxonomy against the then-popular--and biblically

sanctioned--view that the whale was a fish. The immediate dispute was

mundane: whether whale oil was fish oil and therefore subject to state

inspection. But the trial fueled a sensational public debate in which

nothing less than the order of nature--and how we know it--was at stake.

Burnett vividly recreates the trial, during which a parade of

experts--pea-coated whalemen, pompous philosophers, Jacobin

lawyers--took the witness stand, brandishing books, drawings, and

anatomical reports, and telling tall tales from whaling voyages. Falling

in the middle of the century between Linnaeus and Darwin, the trial

dramatized a revolutionary period that saw radical transformations in

the understanding of the natural world. Out went comfortable biblical

categories, and in came new sorting methods based on the minutiae of

interior anatomy--and louche details about the sexual behaviors of God's

creatures.

When leviathan breached in New York in 1818, this strange beast churned

both the natural and social orders--and not everyone would survive.