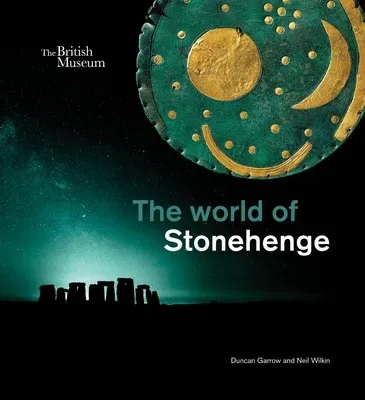

Stonehenge is one of the best known, but most misunderstood, monuments

in the world. Contrary to common belief, it was not a static, unchanging

structure built by shadowy figures or druids. Rather it represents the

cumulative achievement of numerous generations who were woven into a

complex and widespread network of cultural interactions, environmental

change, and belief systems. This publication, which accompanies the

first exhibition about Stonehenge ever staged in London, uses the

monument as a gateway to explore the communities and civilizations

active at the time of its construction and beyond, between 4,000 and

1,000 BCE.

Recent archaeological findings regarding the origin of Stonehenge's

striking 'bluestones' have re-ignited interest in this ancient wonder,

the people who built it, and the beliefs they held. Through the 'iconic'

structure, spectacular objects of precious and exotic material and more

humble, personal objects, authors Duncan Garrow and Neil Wilkin examine

the dramatic cultural and societal shifts that characterized the world

of Stonehenge, including the introduction of farming and development of

metalworking.

Covering a period of thousands of years, the publication traces the

appearance of the first monuments in the landscape of Britain around

4,000 BCE, the arrival of the bluestones from the Preseli Hills in

Pembrokeshire 1,000 years later, all the way up to a remarkable era of

cross-Channel connectivity and trade between 1,500 and 800 BCE.

Through a new study of the enigmatic and beautiful objects made and

circulated during the age of Stonehenge, connections are charted in the

shared religious practices and beliefs of communities from across

Britain, Ireland, and continental Europe. The presence of other stone

and wooden circles hundreds of miles from Salisbury Plain - including

Seahenge, discovered on a beach in Norfolk in 1998 - is further evidence

of these shared ways of thinking.

At a critical moment in the narrative of Stonehenge, around 2,500 BCE,

the significance of the cosmos and the heavens expressed through the

construction of stone circles and megalithic passage tombs began to wane

and portable objects gained increasing importance. This key

transformation is demonstrated by a highlight object from Germany: the

Nebra Sky Disc, a bronze disc inlaid with gold symbols believed to

represent the Sun, a crescent moon and the Pleiades constellation. More

modest items found in tombs, burials and settlements are no less

important in shedding light on the development of ideas relating to

identity, religious practices, and relationships between the living and

dead.

Monuments such as Stonehenge cannot be understood in isolation.

Stonehenge was not always a static, monolithic structure: over

generations it was adapted and added to by communities that changed and

developed the landscape on which it still stands today.