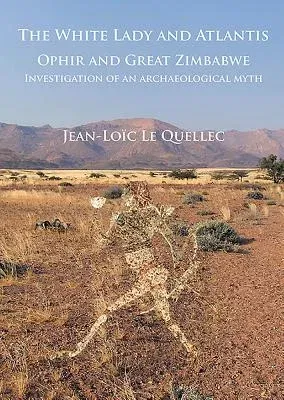

This meticulous investigation, based around a famous rock image, the

'White Lady', makes it possible to take stock of the mythical

presuppositions that infuse a great deal of scientific research,

especially in the case of rock art studies. It also highlights the

existence of some surprising bridges between scholarly works and

literary or artistic productions (novels, films, comic strips, adventure

tales). The examination of the abbe Breuil's archives and correspondence

shows that the primary motivation of the work he carried out in southern

Africa like that of his pupil Henri Lhote in the Tassili was the search

for ancient, vanished 'white' colonies which were established, in

prehistory, in the heart of the dark continent. Both Breuil and Lhote

found paintings on African rocks that, in their view, depicted 'white

women' who were immediately interpreted as goddesses or queens of the

ancient kingdoms of which they believed they had found the vestiges. In

doing this, they were reviving and nourishing two myths at the same

time: that of a Saharan Atlantis for Henri Lhote and, for the abbe, that

of the identification of the great ruins of Zimbabwe with the mythical

city of Ophir from which, according to the Bible, King Solomon derived

his fabulous wealth. With hindsight we can now see very clearly that

their theories were merely a clumsy reflection of the ideas of their

time, particularly in the colonial context of the Sahara and in the

apartheid of South Africa. Without their knowledge, these two scholars'

scientific production was used to justify the white presence in Africa,

and it was widely manipulated to that end. And yet recent studies have

demonstrated that the 'White Lady' who so fascinated the abbe Breuil was

in reality neither white nor even a woman. One question remains: if such

an interpenetration of science and myth in the service of politics was

possible in the mid-20th century, could it happen today?