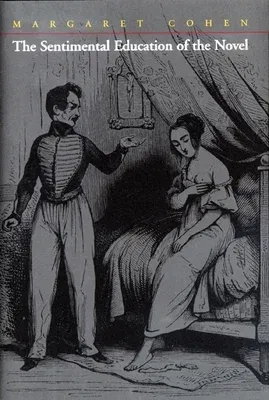

The nineteenth-century French novel has long been seen as the heroic

production of great men, who confronted in their works the social

consequences of the French Revolution. And it is true that French

realism, especially as developed by Balzac and Stendhal, was one of the

most influential novelistic forms ever invented. Margaret Cohen,

however, challenges the traditional account of the genesis of realism by

returning Balzac and Stendhal to the forgotten novelistic contexts of

their time. Reconstructing a key formative period for the novel, she

shows how realist codes emerged in a "hostile take-over" of a

prestigious contemporary sentimental practice of the novel, which was

almost completely dominated by women writers.

Cohen draws on impressive archival research, resurrecting scores of

forgotten nineteenth-century novels, to demonstrate that the codes most

closely identified with realism were actually the invention of

sentimentality, a powerful aesthetic of emerging liberal-democratic

society, although Balzac and Stendhal trivialized sentimental works by

associating them with "frivolous" women writers and readers. Attention

to these gendered struggles over genre explains why women were not

pioneers of realism in France during the nineteenth century, a situation

that contrasts with England, where women writers played a formative role

in inventing the modern realist novel. Cohen argues that to understand

how literary codes respond to material factors, it is imperative to see

how such factors take shape within the literary field as well as within

society as a whole. The book also proposes that attention to literature

as a social institution will help critics resolve the current, vital

question of how to practice literary history in the wake of

poststructuralism.