Alisha Rankin

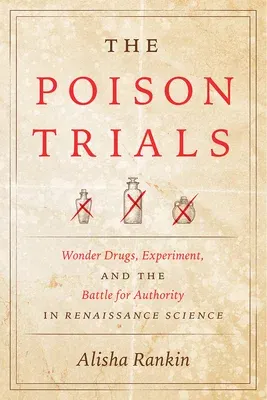

(Author)The Poison Trials: Wonder Drugs, Experiment, and the Battle for Authority in Renaissance SciencePaperback, 1 January 2021

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

Only 2 left

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Synthesis

Print Length

312 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of Chicago Press

Date Published

1 Jan 2021

ISBN-10

022674485X

ISBN-13

9780226744858

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

1 January 2021

Dimensions:

22.61 x

15.24 x

2.03 cm

ISBN-10:

022674485X

ISBN-13:

9780226744858

Language:

English

Pages:

312

Publisher:

Series:

Weight:

521.63 gm