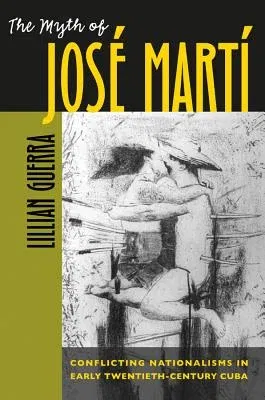

Lillian Guerra

(Author)The Myth of José Martí: Conflicting Nationalisms in Early Twentieth-Century CubaPaperback, 31 March 2005

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Envisioning Cuba

Part of Series

Envisioning Cuba (Paperback)

Print Length

328 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of North Carolina Press

Date Published

31 Mar 2005

ISBN-10

0807855901

ISBN-13

9780807855904

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

31 March 2005

Dimensions:

23.27 x

15.8 x

1.98 cm

ISBN-10:

0807855901

ISBN-13:

9780807855904

Language:

English

Location:

Chapel Hill

Pages:

328

Publisher:

Weight:

471.74 gm