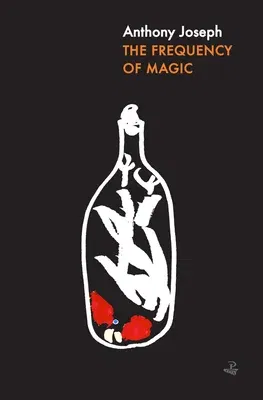

Anthony Joseph

(Author)The Frequency of MagicPaperback, 12 March 2020

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

Only 3 left

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Print Length

306 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Peepal Tree Press

Date Published

12 Mar 2020

ISBN-10

1845234553

ISBN-13

9781845234553

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

12 March 2020

Dimensions:

20.32 x

13.46 x

2.54 cm

ISBN-10:

1845234553

ISBN-13:

9781845234553

Language:

English

Pages:

306

Publisher:

Weight:

385.55 gm