Jacob Steere-Williams

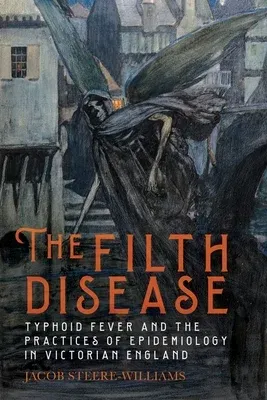

(Author)The Filth Disease: Typhoid Fever and the Practices of Epidemiology in Victorian EnglandHardcover, 15 November 2020

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Rochester Studies in Medical History

Print Length

340 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of Rochester Press

Date Published

15 Nov 2020

ISBN-10

1648250025

ISBN-13

9781648250026

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Hardcover

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

15 November 2020

Dimensions:

22.86 x

15.24 x

2.06 cm

ISBN-10:

1648250025

ISBN-13:

9781648250026

Language:

English

Location:

Rochester

Pages:

340

Publisher:

Weight:

625.96 gm