Some years ago, David Freedberg opened a dusty cupboard at Windsor

Castle and discovered hundreds of vividly colored, masterfully precise

drawings of all sorts of plants and animals from the Old and New Worlds.

Coming upon thousands more drawings like them across Europe, Freedberg

finally traced them all back to a little-known scientific organization

from seventeenth-century Italy called the Academy of Linceans (or

Lynxes).

Founded by Prince Federico Cesi in 1603, the Linceans took as their task

nothing less than the documentation and classification of all of nature

in pictorial form. In this first book-length study of the Linceans to

appear in English, Freedberg focuses especially on their unprecedented

use of drawings based on microscopic observation and other new

techniques of visualization. Where previous thinkers had classified

objects based mainly on similarities of external appearance, the

Linceans instead turned increasingly to sectioning, dissection, and

observation of internal structures. They applied their new research

techniques to an incredible variety of subjects, from the objects in the

heavens studied by their most famous (and infamous) member Galileo

Galilei--whom they supported at the most critical moments of his

career--to the flora and fauna of Mexico, bees, fossils, and the

reproduction of plants and fungi. But by demonstrating the inadequacy of

surface structures for ordering the world, the Linceans unwittingly

planted the seeds for the demise of their own favorite method--visual

description-as a mode of scientific classification.

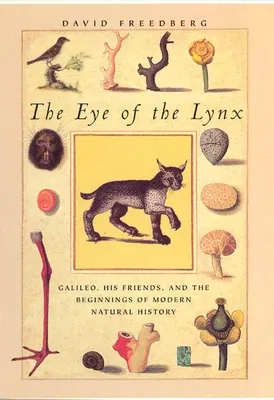

Profusely illustrated and engagingly written, Eye of the Lynx uncovers

a crucial episode in the development of visual representation and

natural history. And perhaps as important, it offers readers a dazzling

array of early modern drawings, from magnificently depicted birds and

flowers to frogs in amber, monstrously misshapen citrus fruits, and

more.