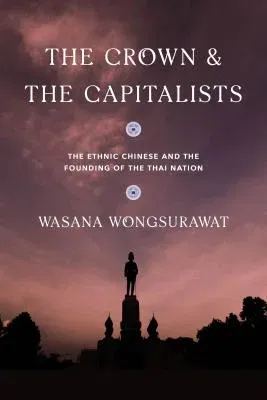

Wasana Wongsurawat

(Author)The Crown and the Capitalists: The Ethnic Chinese and the Founding of the Thai NationPaperback, 18 November 2019

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

Only 2 left

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Critical Dialogues in Southeast Asian Studies

Print Length

216 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of Washington Press

Date Published

18 Nov 2019

ISBN-10

0295746246

ISBN-13

9780295746241

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

18 November 2019

Dimensions:

22.61 x

15.24 x

2.03 cm

ISBN-10:

0295746246

ISBN-13:

9780295746241

Language:

English

Location:

Seattle

Pages:

216

Publisher:

Weight:

294.83 gm