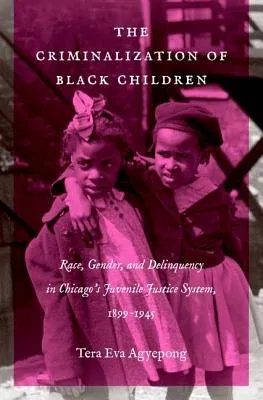

Tera Eva Agyepong

(Author)The Criminalization of Black Children: Race, Gender, and Delinquency in Chicago's Juvenile Justice System, 1899-1945Paperback, 9 April 2018

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Justice, Power, and Politics

Print Length

196 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of North Carolina Press

Date Published

9 Apr 2018

ISBN-10

1469636441

ISBN-13

9781469636443

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

9 April 2018

Dimensions:

23.39 x

15.6 x

1.14 cm

ISBN-10:

1469636441

ISBN-13:

9781469636443

Language:

English

Location:

Chapel Hill

Pages:

196

Publisher:

Series:

Weight:

312.98 gm