When Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in 1837 that "Our Age is Ocular," he

offered a succinct assessment of antebellum America's cultural,

commercial, and physiological preoccupation with sight. In the early

nineteenth century, the American city's visual culture was manifest in

pamphlets, newspapers, painting exhibitions, and spectacular

entertainments; businesses promoted their wares to consumers on the move

with broadsides, posters, and signboards; and advances in

ophthalmological sciences linked the mechanics of vision to the

physiological functions of the human body. Within this crowded visual

field, sight circulated as a metaphor, as a physiological process, and

as a commercial commodity. Out of the intersection of these various

discourses and practices emerged an entirely new understanding of

vision.

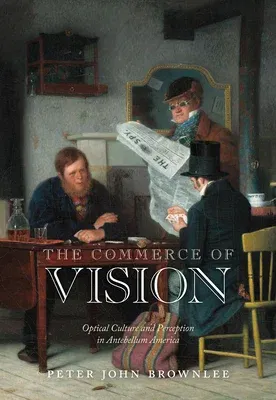

The Commerce of Vision integrates cultural history, art history, and

material culture studies to explore how vision was understood and

experienced in the first half of the nineteenth century. Peter John

Brownlee examines a wide selection of objects and practices that

demonstrate the contemporary preoccupation with ocular culture and

accurate vision: from the birth of ophthalmic surgery to the business of

opticians, from the typography used by urban sign painters and job

printers to the explosion of daguerreotypes and other visual forms, and

from the novels of Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville to the genre

paintings of Richard Caton Woodville and Francis Edmonds. In response to

this expanding visual culture, antebellum Americans cultivated new

perceptual practices, habits, and aptitudes. At the same time, however,

new visual experiences became quickly integrated with the machinery of

commodity production and highlighted the physical shortcomings of sight,

as well as nascent ethical shortcomings of a surface-based culture.

Through its theoretically acute and extensively researched analysis,

The Commerce of Vision synthesizes the broad culturing of vision in

antebellum America.