rowth and form of marine organisms inhabiting hard substrata, the

G"marine sessile organisms", ischaracterized by anumber ofremarkable

properties. One remarkable feature of these organisms is that many

ofthem can be characterizedasmodularorganisms. Modularorganisms are

typically built ofrepeated units, the modules, which might be a polyp in

a coral colony or afrond in seaweeds. In most cases, the modulehas

adistinctive form, while the growth form of the entire colony is

frequently an indeterminate form. Indeterminategrowthindicatesthatthe

same growthprocess mayresult in an infinite

numberofdifferentrealizations ofthe growthform.This isincontrast to

unitaryorganisms such asvertebrates and insects, in which a

single-celled stage develops into a well-defined, determinate structure.

In many cases the growth process in modular organisms leads to complex

shapes, which are often quite difficult to describe in words. In most of

the biological literature these forms are only described in

qualitativeand rather vague terms, such as

"thinlybranching","tree-shaped" and "irregularlybranching". Anothermajor

characteristic ofmarine sessile organisms is that there is

frequentlyastrongimpactofthe physical environmenton the growthprocess,

leading to a variety of growth forms. Growth by accumulation of modules

allows the organism to fit its shape to its environment i.e., have

plasticity. In many seaweeds, sponges, and corals, differences in

exposure to water movement cause significant changes in morphology.

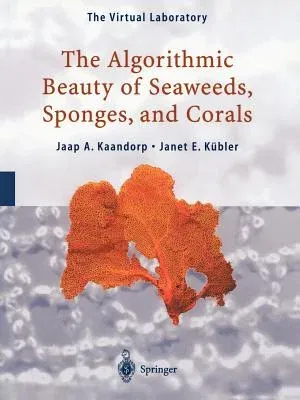

Agood example of this plasticity is the Indo-Pacific stony coral

Pocillopora damicornis(Veron and Pichon 1976) shown in Plg.r.i. In very

sheltered environments, this species has a thin-branching growth form.

The growth form gradually transforms to a more compact shape when the

exposure to water movement increases.