In our first book, we explored the impact of the fighting on the

landscape of the Western Front - showing how the physical effects of war

have left indelible traces; in this book, we follow the same theme, but

from a different perspective. The Gallipoli campaign was planned in

early 1915 - an imaginative, but flawed attempt to overcome the

stalemate in France and Flanders. The idea was Churchill's: to force the

narrow straits of the Dardanelles by naval power alone - a romantic

notion for a generation schooled in the great myths of the Ancient World

and the omnipotent power of the British Empire. Rupert Brooke was one of

them: 'It's too wonderful for belief. I had not imagined Fate could be

so kind. Will Hero's Tower crumble under the 15-inch guns? .... Shall I

loot mosaics from St Sophia, and Turkish Delight and carpets? Should we

be a Turning Point in History? Oh God! I've never been quite so happy in

my life I think. I suddenly realise that the ambition of my life has

been ... to go on a military expedition to Constantinople'.

The reality was different: the navy failed to get through the straits.

The only option was to land troops on the Gallipoli Peninsula to destroy

the Turkish guns, but even then it was thought that all of this could be

achieved without much effort. Gallipoli was seen as a sideshow, where

the benefits of victory were never matched by the resources needed. The

British underestimated their enemy - assuming that old naval ships,

inexperienced troops and senior commanders from an era of colonial

warfare was all that was needed; they were wrong.

Rupert Brooke died on 23 April 1915 - two days before the landings - and

the campaign was to last for eight months to great cost and no effect.

The Turkish defense was stalwart and competent, and fighting was at

close quarters in appalling conditions across deep ravines, on ridges

and on plateaus. The objectives - the high ground a few miles inland -

were never reached by the attackers, who remained trapped in an alien

and narrow 'no man's land' thousands of miles from home. The romanticism

of this place evaporated in the face of disease, a lack of food and

water and in death.

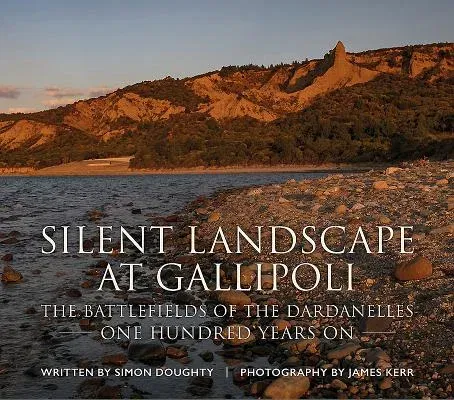

Gallipoli was abandoned by the British in early 1916. Given the nature

of the fighting, it might be assumed, following such a short campaign,

the evidence of war has long since disappeared, but it has not: the

natural features over which the fighting took place remain, as do the

shadows of trenches; the skeletal-like hulls of landing craft on the

shoreline; and the wrecks of more than 200 ships on the seabed beyond.

There is a discernible presence here; the landscape has absorbed the

events that took place here a century ago.

Gallipoli lies at the gates to the East and just a few miles north of

the ancient City of Troy. For just a short time in early 1915, it seemed

that this place held the key to an imagined world beyond; it did not,

and the only true victors were the Turks. For the British, it was a

dreadful defeat with no consolation, while for the Australians and New

Zealanders, it was a defining moment in their journey to national

identity. Today, the battlefield is almost untouched by time - a lonely

and haunted place... remote under an idyllic Aegean sky.