In this comprehensive history of women's antislavery petitions addressed

to Congress, Susan Zaeske argues that by petitioning, women not only

contributed significantly to the movement to abolish slavery but also

made important strides toward securing their own rights and transforming

their own political identity.

By analyzing the language of women's antislavery petitions, speeches

calling women to petition, congressional debates, and public reaction to

women's petitions from 1831 to 1865, Zaeske reconstructs and interprets

debates over the meaning of female citizenship. At the beginning of

their political campaign in 1835 women tended to disavow the political

nature of their petitioning, but by the 1840s they routinely asserted

women's right to make political demands of their representatives. This

rhetorical change, from a tone of humility to one of insistence,

reflected an ongoing transformation in the political identity of

petition signers, as they came to view themselves not as subjects but as

citizens. Having encouraged women's involvement in national politics,

women's antislavery petitioning created an appetite for further

political participation that spurred countless women after the Civil War

and during the first decades of the twentieth century to promote causes

such as temperance, anti-lynching laws, and woman suffrage.

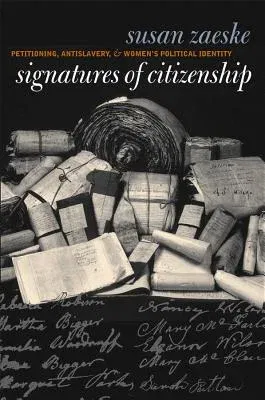

Petitions representing only a fraction of those signed by hundreds of

thousands of men and women calling for the abolition of slavery received

by Congress between 1831 and 1863. Courtesy of the Foundation for the

National Archives.