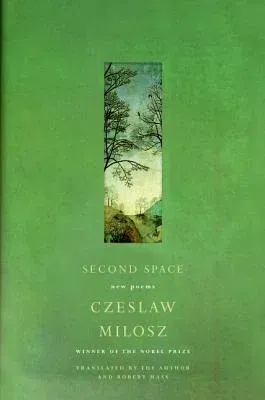

Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz's most recent collection Second Space

marks a new stage in one of the great poetic pilgrimages of our time.

Few poets have inhabited the land of old age as long or energetically as

Milosz, for whom this territory holds both openings and closings,

affirmations as well as losses. "Not soon, as late as the approach of my

ninetieth year, / I felt a door opening in me and I entered / the

clarity of early morning," he writes in "Late Ripeness." Elsewhere he

laments the loss of his voracious vision -- "My wondrously quick eyes,

you saw many things, / Lands and cities, islands and oceans" -- only to

discover a new light that defies the limits of physical sight: "Without

eyes, my gaze is fixed on one bright point, / That grows large and takes

me in."

Second Space is typically capacious in the range of voices, forms, and

subjects it embraces. It moves seamlessly from dramatic monologues to

theological treatises, from philosophy and history to epigrams, elegies,

and metaphysical meditations. It is unified by Milosz's ongoing quest to

find the bond linking the things of this world with the order of a

"second space," shaped not by necessity, but grace. Second Space

invites us to accompany a self-proclaimed "apprentice" on this

extraordinary quest. In "Treatise on Theology," Milosz calls himself "a

one day's master." He is, of course, far more than this. Second Space

reveals an artist peerless both in his capacity to confront the world's

suffering and in his eagerness to embrace its joys: "Sun. And sky. And

in the sky white clouds. / Only now everything cried to him: Eurydice! /

How will I live without you, my consoling one! / But there was a

fragrant scent of herbs, the low humming of bees, / And he fell asleep

with his cheek on the sun-warmed earth."