Caesar's war machine clashes with the fearsome tribes of Gaul, forever

changing the character of the region and laying the groundwork for the

rise of the Roman Empire.

In the manner of many Roman generals, Caesar would write his domestic

political ambitions in the blood and treasure of foreign lands. His

governorship of Cisalpine Gaul gave him the opportunity to demonstrate

the greatness of his character to the people of Rome through the

subjugation of those outside Rome's borders. The fact that the main

account of the subsequent wars in Gaul was written by Caesar himself -

by far the most detailed history of the subject, with new reports issued

annually for the eager audience at home -is no accident.

The Roman Army of the late Republic had long been in the process of

structural and change, moving towards the all-volunteer permanent

standing force that would for centuries be the bulwark of the coming

Empire. Well-armed and armored, this professional army was trained to

operate within self-supporting legions, with auxiliaries employed in

roles the legions lacked such as light troops or cavalry. The Roman

legions were in many ways a modern force, with formations designed

around tactical goals and held together by discipline, training and

common purpose.

The armies fielded by the tribes of Gaul were for the most part lightly

armed and armored, with fine cavalry and a well-deserved reputation for

ferocity. As might be expected from a region made up of different tribes

with a range of needs and interests, there was no consensus on how to

make war, though when large armies were gathered it was usually with the

express purpose of bringing the enemy to heel in a pitched battle. For

most Gauls - and certainly the military elites of the tribes - battle

was an opportunity to prove their personal courage and skill, raising

their status in the eyes of friends and foes alike.

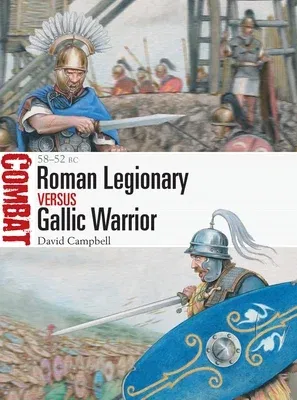

Fully illustrated, this study investigates the Roman and Gallic forces

pitched into combat in three battles: Bibracte (58 BC), Sabis (57 BC)

and Gergovia/Alesia (52 BC). Although charismatic Gallic leaders did

rise up - notably Dumnorix of the Aedui and later Vercingetorix of the

Arverni - and proved to be men capable of bringing together forces that

had the prospect of checking Caesar's ambitions in the bloodiest of

ways, it would not be enough. For Caesar his war against the Gauls

provided him with enormous power and the springboard he needed to make

Rome his own, though his many domestic enemies would ensure that he did

not long enjoy his success.