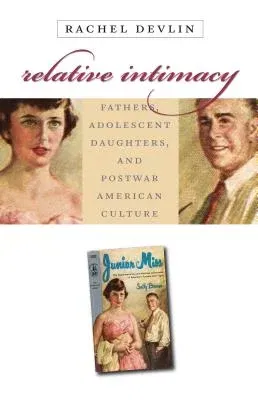

Rachel Devlin

(Author)Relative Intimacy: Fathers, Adolescent Daughters, and Postwar American CulturePaperback, 13 June 2005

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Gender and American Culture

Part of Series

Gender and American Culture (Paperback)

Print Length

272 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of North Carolina Press

Date Published

13 Jun 2005

ISBN-10

0807856053

ISBN-13

9780807856055

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

13 June 2005

Dimensions:

21.64 x

14.12 x

1.7 cm

ISBN-10:

0807856053

ISBN-13:

9780807856055

Language:

English

Location:

Chapel Hill

Pages:

272

Publisher:

Weight:

322.05 gm