When Ojibwe historian Brenda Child uncovered the Bureau of Indian

Affairs file on her grandparents, it was an eye-opening experience. The

correspondence, full of incendiary comments on their morals and

character, demonstrated the breathtakingly intrusive power of federal

agents in the early twentieth century.

While telling her own family's stories from the Red Lake Reservation, as

well as stories of Ojibwe people around the Great Lakes, Child examines

the disruptions and the continuities in daily work, family life, and

culture faced by Ojibwe people of Child's grandparents' generation--a

generation raised with traditional lifeways in that remote area. The

challenges were great: there were few opportunities for work. Government

employees and programs controlled reservation economies and opposed

traditional practices. Nevertheless, Ojibwe men and women--fully modern

workers who carried with them rich traditions of culture and

work--patched together sources of income and took on new roles as labor

demands changed through World War I and the Depression.

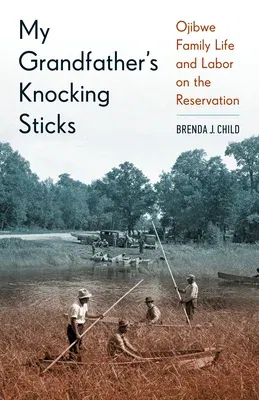

Child writes of men knocking rice at wild rice camps, work customarily

done by women; a woman who turns to fishing and bootlegging when her

husband is unable to work. She also recounts that one hundred years ago

in 1918-1919, when the global influenza pandemic killed millions

worldwide, including thousands of Native Americans, a revolutionary new

tradition of healing and anti-colonial resistance emerged in Ojibwe

communities in North America: the jingle dress dance. All of them, faced

with dispossession and pressure to adopt new ways, managed to retain and

pass on their Ojibwe identity and culture to their children.