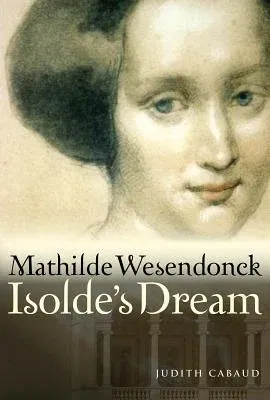

Judith Cabaud

(Author)Mathilde Wesendonck, Isolde's DreamHardcover, 1 August 2017

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Amadeus

Print Length

296 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Amadeus

Date Published

1 Aug 2017

ISBN-10

1574674919

ISBN-13

9781574674910

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Hardcover

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

1 August 2017

Dimensions:

22.61 x

15.75 x

2.29 cm

ISBN-10:

1574674919

ISBN-13:

9781574674910

Language:

English

Pages:

296

Publisher:

Series:

Weight:

635.03 gm