Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) was proud to call himself an American

artist, but he dreamed of travel to Europe, believing instinctively that

he would learn more there than would be possible in his home state of

Maine or even in New York. In 1909 Alfred Stieglitz gave Hartley his

first solo exhibition in New York, and a second successful show three

years later enabled him to head to Europe, where he spent time in Paris,

Berlin and Munich. His rise to prominence as a specifically American

modernist was based largely on the visual ideas and influences that he

encountered in these vibrant cities, which he then synthesized through

his own New England point of view. Hartley, who was by nature something

of a loner, never lost his wanderlust, and throughout his life found

inspiration in many other landscapes and cultures, including in southern

France, Italy, Bermuda, Mexico and Canada.

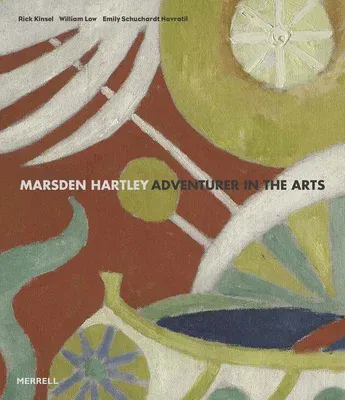

Marsden Hartley: Adventurer in the Arts, published to coincide with an

exhibition opening at the Vilcek Foundation in New York, offers a fresh

appraisal of a pioneering modernist whose work continues to be

celebrated for its spirituality, experimentation and innovation. Rick

Kinsel's introduction provides an overview of the manifold ways in which

Hartley's travels shaped his artistic vision, from experiencing the

latest art in Paris and finding a mentor there in Gertrude Stein to

meeting members of the Blaue Reiter group in Germany and developing an

interest in both Prussian military pageantry and Bavarian folk art; from

becoming fascinated with ancient Aztec and Mayan cultures while in

Mexico to being inspired by the traditional pueblo life of the Native

Americans of the Southwest.

William Low surveys items from the Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection

of Bates College Museum in Maine - including memorabilia from the

artist's travels and artefacts reflecting his diverse spiritual

interests - and explains how they aid our understanding of Hartley's

motivation and passions. Among them are a photograph album tracing the

course of Hartley's peripatetic life from 1908 to 1930 and a notebook of

'Color Exercises', both of which are reproduced in full. Emily

Schuchardt Navratil considers how Hartley's desire for escape was

reflected in his love of the circus, a recurrent theme in his paintings,

drawings and writings. He was enthralled by the spectacle and the

nomadic existence, and he imagined circus performers to be members of

his own wandering troupe. For fifteen years he worked on a book devoted

to the subject, but it was left unfinished at his death; an 18-page

typescript version is reproduced here in its entirety.

Kinsel then explores Hartley's painting Canoe (Schiff), created in

Berlin in 1915 as part of his Amerika series of brightly coloured

works defined by imagery drawn from both Native American material

culture and German folk art. For Hartley, these paintings represented a

dual cultural identity. The main part of the book, by Navratil, features

some 100 paintings, drawings, photographs and postcards, arranged into

seven country- or state-themed sections, with a concluding section on

Hartley's personal possessions, which - because he had no permanent home

of his own - held extraordinary significance for him.