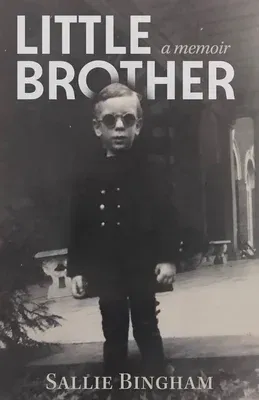

Sallie Bingham

(Author)Little BrotherPaperback, 17 May 2022

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Print Length

176 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Sarabande Books

Date Published

17 May 2022

ISBN-10

1946448982

ISBN-13

9781946448989

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

CA

Date Published:

17 May 2022

Dimensions:

21.41 x

13.79 x

1.4 cm

Genre:

Feminine

ISBN-10:

1946448982

ISBN-13:

9781946448989

Language:

English

Pages:

176

Publisher:

Weight:

204.12 gm