A visual discovery of a land not typically thought of in California,

this debut looks at the historic Santa Maria Valley, known for its

vineyards and agriculture, and associates it with the environmental cost

of human need.

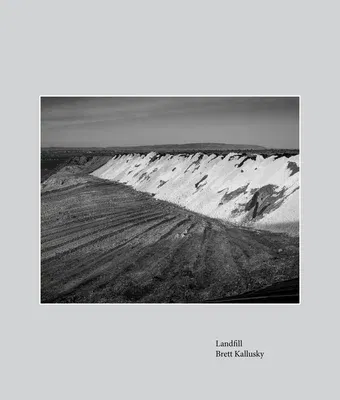

Landfill is a collection of eye-opening photographs made by Brett

Kallusky in central California's historic Santa Maria Valley. This body

of work, however, directs our attention not to the world-renowned

vineyards on the hillsides, a legacy of Spanish times, but to the vast

agricultural production of row crops on the valley floor and the

millions of tons of garbage and industrial refuse that finds its way to

the regional landfill. The photographs of the landfill and the Valley

reveal scenes that are literally hidden from public view and knowledge,

underscoring their nature as documentary evidence of what is involved in

growing crops that feed the nation.

Kallusky's interest does not end there, for his depiction of this famous

California landscape creates an opportunity for contemplative reflection

of our complicit involvement in land use here, if only by eating the

strawberries, carrots, and cauliflower that are grown in the Valley and

transported to grocery stores throughout the U.S. Despite the cool

formalism and detached documentary style of Kallusky's pictures,

assembled and sequenced as they are, he engages us in an extended

consideration of our relationship with the land, drawing viewers into a

new understanding of this place.

Given the Valley's location near the oil-rich Pacific waters outside

Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara Counties, which

comprise the Valley, have had their fair share of calamitous

environmental events and contaminated locations associated with oil.

These include, most recently, the superfund site in Casmalia, where 4.5

billion pounds of petroleum-based and other hazardous waste were

transported to a disposal facility there from 1973 until its closing in

1989, and the massive out-of-control Union Oil Tank Fires at Avila Beach

in 1908 and San Luis Obispo in 1926, where three workers were killed.

Kallusky renders these places anew.

Addressing the current, human-centered epoch known as the Anthropocene,

the quiet but powerful imagery of Kallusky's Landfill examines the

important connection between how the land is used and regarded. The

Santa Maria landscape reveals who we are, as Kallusky's photographs

bring its invisible spaces into full view, showing how the earth

supports our food needs on a massive scale, fueling a cyclical engine of

consumption, waste, and renewal. The Santa Maria Valley is thus a

microcosm of America with ramifications far beyond its geographical

boundaries. What is left in the wake of that system to which we all

belong? In Landfill, the landscapes we create tell it all.