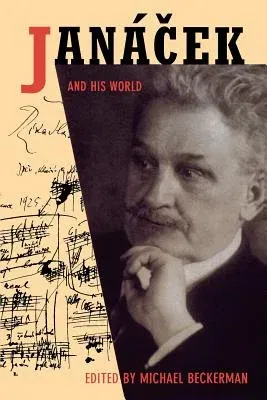

Once thought to be a provincial composer of only passing interest to

eccentrics, Leos Janácek (1854-1928) is now widely acknowledged as one

of the most powerful and original creative figures of his time. Banned

for all purposes from the Prague stage until the age of 62, and unable

to make it even out of the provincial capital of Brno, his operas are

now performed in dynamic productions throughout the globe. This volume

brings together some of the world's foremost Janácek scholars to look

closely at a broad range of issues surrounding his life and work.

Representing the latest in Janácek scholarship, the essays are

accompanied by newly translated writings by the composer himself.

The collection opens with an essay by Leon Botstein who clarifies and

amplifies how Max Brod contributed to Janácek 's international success

by serving as "point man" between Czechs and Germans, Jews and non-Jews.

John Tyrrell, the dean of Janácek scholars, distills more than thirty

years of research in "How Janácek Composed Operas," while Diane Paige

considers Janácek's liason with a married woman and the question of the

artist's muse. Geoffrey Chew places the idea of the adulterous muse in

the larger context of Czech fin de siècle decadence in his thoroughgoing

consideration of Janácek's problematic opera Osud. Derek Katz examines

the problems encountered by Janácek's satirically patriotic "Excursions

of Mr. Broucek" in the post-World War I era of Czechoslovak nationalism,

while Paul Wingfield mounts a defense of Janácek against allegations of

cruelty in his wife's memoirs. In the final essay, Michael Beckerman

asks how much true history can be culled from one of Janácek's business

cards.

The book then turns to writings by Janácek previously unpublished in

English. These not only include fascinating essays on Naturalism, opera

direction, and Tristan and Isolde, but four impressionistic chronicles

of the "speech melodies" of daily life. They provide insight into

Janácek's revolutionary method of composition, and give us the closest

thing we will ever have to the "heard" record of a Czech pre-war past-or

any past, for that matter.