The fear of oblivion obsessed medieval and early modern Europe. Stone,

wood, cloth, parchment, and paper all provided media onto which writing

was inscribed as a way to ward off loss. And the task was not easy in a

world in which writing could be destroyed, manuscripts lost, or books

menaced with destruction. Paradoxically, the successful spread of

printing posed another danger, namely, that an uncontrollable

proliferation of textual materials, of matter without order or limit,

might allow useless texts to multiply and smother thought. Not

everything written was destined for the archives; indeed, much was

written on surfaces that allowed one to write, erase, then write again.

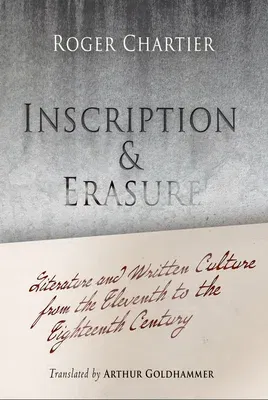

In Inscription and Erasure, Roger Chartier seeks to demonstrate how

the tension between these two concerns played out in the imaginative

works of their times. Chartier examines how authors transformed the

material realities of writing and publication into an aesthetic resource

exploited for poetic, dramatic, or narrative ends. The process that gave

form to writing in its various modes--public or private, ephemeral or

permanent--thus became the very material of literary invention.

Chartier's chapters follow a thread of reading and interpretation that

takes us from the twelfth-century French poet Baudri of Bourgueil,

sketching out his poems on wax tablets before they are committed to

parchment, through Cervantes in the seventeenth century, who places a

"book of memory," in which poems and letters are to be recopied, in the

path of his fictional Don Quixote.