Tanya Hart

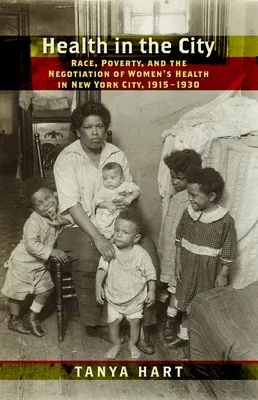

(Author)Health in the City: Race, Poverty, and the Negotiation of Women's Health in New York City, 1915-1930Hardcover, 1 May 2015

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

Only 2 left

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Culture, Labor, History

Print Length

336 pages

Language

English

Publisher

New York University Press

Date Published

1 May 2015

ISBN-10

1479867993

ISBN-13

9781479867998

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Hardcover

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

1 May 2015

Dimensions:

23.11 x

15.75 x

2.54 cm

Genre:

Medical/Medicine Aspects

ISBN-10:

1479867993

ISBN-13:

9781479867998

Language:

English

Location:

New York

Pages:

336

Publisher:

Series:

Weight:

544.31 gm