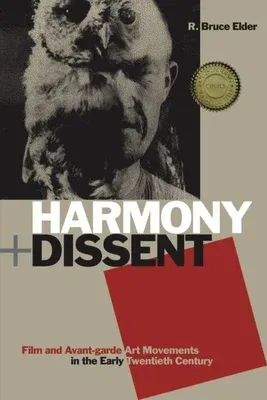

R Bruce Elder

(Author)Harmony + Dissent: Film and Avant-Garde Art Movements in the Early Twentieth CenturyPaperback, 22 April 2010

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Film and Media Studies

Print Length

540 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Wilfrid Laurier University Press

Date Published

22 Apr 2010

ISBN-10

1554582261

ISBN-13

9781554582266

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

CA

Date Published:

22 April 2010

Dimensions:

21.95 x

14.94 x

3.15 cm

ISBN-10:

1554582261

ISBN-13:

9781554582266

Language:

English

Location:

Waterloo, ON

Pages:

540

Publisher:

Series:

Weight:

725.75 gm