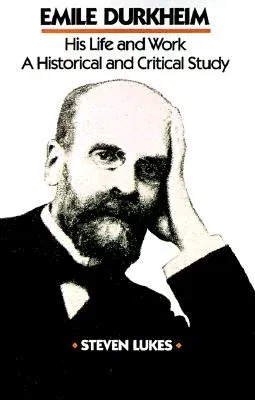

Steven Lukes

(Author)Emile Durkheim: His Life and Work: A Historical and Critical Study (Anniversary)Paperback - Anniversary, 1 August 1985

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Print Length

676 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Stanford University Press

Date Published

1 Aug 1985

ISBN-10

0804712832

ISBN-13

9780804712835

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Edition:

Anniversary

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

1 August 1985

Dimensions:

21.34 x

13.97 x

4.06 cm

ISBN-10:

0804712832

ISBN-13:

9780804712835

Language:

English

Location:

Stanford, CA

Pages:

676

Publisher:

Weight:

793.79 gm