On the afternoon of 6 June 1889, a fire in a cabinet shop in downtown

Seattle spread to destroy more than thirty downtown blocks covering 116

acres. Disaster soon became opportunity as Seattle's citizens turned

their full energies to rebuilding: widening and regrading streets,

laying new water pipes and sewer lines, promulgating a new building

ordinance requiring construction in the commercial core, and creating a

new professional fire department. A remarkable number of buildings, most

located in Seattle's present-day Pioneer Square Historic District, were

permitted within a few months and constructed within a few years of the

Great Seattle Fire. As a result, the post-fire rebuilding of Seattle

offers an extraordinarily focused case study of late-nineteenth-century

American urban architecture.

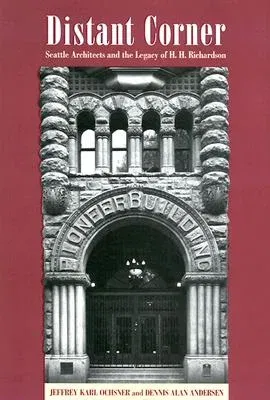

Seattle's architects, seeking design solutions that would meet the new

requirements, most often found them in the Romanesque Revival mode of

the country's most famous architect, Henry Hobson Richardson. In October

1889, Elmer Fisher, Seattle's most prolific post-fire architect,

specifically cited the example of H. H. Richardson in describing the

city's new buildings. In contrast to Victorian Gothic, Second Empire,

and other mid-nineteenth-century architectural styles, Richardson's

Romanesque Revival vocabulary of relatively unadorned stone and brick

with round-arched openings conveyed strength and stability without

elaborate decorative treatment. For Seattle's fire-conscious architects

it offered a clear architectural system that could be applied to a

variety of building types - including office blocks, warehouses, and

hotels - and ensure a safer, progressive, and more visually coherent

metropolitan center.

Distant Corner examines the brief but powerful influence of H. H.

Richardson on the building of America's cities, and his specific

influence on the architects charged with rebuilding the post-fire city

of Seattle. Chapters on the pre-fire city and its architecture, the

technologies and tools available to designers and builders, and the rise

of Richardson and his role in defining a new American architecture

provide a context for examining the work of the city's architects.

Seattle's leading pre- and post-fire architects - William Boone, Elmer

Fisher, John Parkinson, Charles Saunders and Edwin Houghton, Willis

Ritchie, Emil DeNeuf, Warren Skillings, and Arthur Chamberlin - are

profiled. Distant Corner describes the new post-fire commercial core

and the emerging network of schools, firehouses, and other public

institutions that helped define Seattle's neighborhoods. It closes with

the sudden collapse of Seattle's economy in the Panic of 1893 and the

ensuing depression that halted the city's building boom, saw the closing

of a number of architects' offices, and forever ended the dominance of

Romanesque Revival in American architecture.

With more than 200 illustrations, detailed endnotes, and an appendix

listing the major works of the city's leading architects, Distant

Corner offers an analysis of both local and national influences that

shaped the architecture of the city in the 1880s and 1890s. It has much

to offer those interested in Seattle's early history, the building of

the city, and the preservation of its architecture. Because this period

of American architecture has received only limited study, it is also of

importance for those interested in the influence of Boston-based H. H.

Richardson and his contemporaries on American architecture at the end of

the nineteenth century.