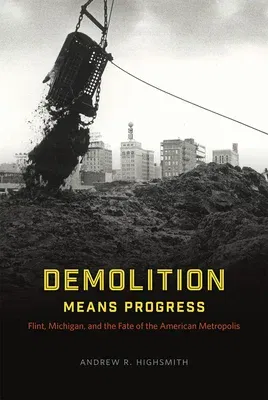

In 1997, after General Motors shuttered a massive complex of factories

in the gritty industrial city of Flint, Michigan, signs were placed

around the empty facility reading, "Demolition Means Progress,"

suggesting that the struggling metropolis could not move forward to

greatness until the old plants met the wrecking ball. Much more than a

trite corporate slogan, the phrase encapsulates the operating ethos of

the nation's metropolitan leadership from at least the 1930s to the

present. Throughout, the leaders of Flint and other municipalities

repeatedly tried to revitalize their communities by demolishing outdated

and inefficient structures and institutions and overseeing numerous

urban renewal campaigns--many of which yielded only more impoverished

and more divided metropolises. After decades of these efforts, the dawn

of the twenty-first century found Flint one of the most racially

segregated and economically polarized metropolitan areas in the nation.

In one of the most comprehensive works yet written on the history of

inequality and metropolitan development in modern America, Andrew R.

Highsmith uses the case of Flint to explain how the perennial quest for

urban renewal--even more than white flight, corporate abandonment, and

other forces--contributed to mass suburbanization, racial and economic

division, deindustrialization, and political fragmentation. Challenging

much of the conventional wisdom about structural inequality and the

roots of the nation's "urban crisis," Demolition Means Progress shows

in vivid detail how public policies and programs designed to revitalize

the Flint area ultimately led to the hardening of social divisions.