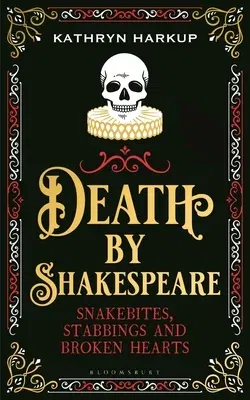

An in-depth look at the science behind the creative methods

Shakespeare used to kill off his characters.

In Death By Shakespeare, Kathryn Harkup, best-selling author of A is

for Arsenic and expert on the more gruesome side of science, turns her

expertise to William Shakespeare and the creative methods he used to

kill off his characters. Is death by snakebite really as serene as

Cleopatra made it seem? How did Juliet appear dead for 72 hours only to

be revived in perfect health? Can you really kill someone by pouring

poison in their ear? How long would it take before Lady Macbeth died

from lack of sleep? Harkup investigates what actual events may have

inspired Shakespeare, what the accepted scientific knowledge of the time

was, and how Elizabethan audiences would have responded to these death

scenes. Death by Shakespeare reveals this and more in a rollercoaster

of Elizabethan carnage, poison, swordplay and bloodshed, with an

occasional death by bear-mauling for good measure.

In the Bard's day death was a part of everyday life. Plague, pestilence

and public executions were a common occurrence, and the chances of

seeing a dead or dying body on the way home from the theater was a

fairly likely scenario. Death is one of the major themes that reoccurs

constantly throughout Shakespeare's canon, and he certainly didn't shy

away from portraying the bloody reality of death on the stage. He didn't

have to invent gruesome or novel ways to kill off his characters when

everyday experience provided plenty of inspiration.

Shakespeare's era was also a time of huge scientific advance. The human

body, its construction and how it was affected by disease came under

scrutiny, overturning more than a thousand years of received Greek

wisdom, and Shakespeare himself hinted at these new scientific

discoveries and medical advances in his writing, such as circulation of

the blood and treatments for syphilis.

Shakespeare found dozens of different ways to kill off his characters,

and audiences today still enjoy the same reactions--shock, sadness,

fear--that they did over 400 years ago when these plays were first

performed. But how realistic are these deaths, and did Shakespeare have

the science to back them up?