In 1940, Hans Augusto Rey and Margret Rey built two bikes, packed what

they could, and fled wartime Paris. Among the possessions they escaped

with was a manuscript that would later become one of the most celebrated

books in children's literature--Curious George. Since his debut in

1941, the mischievous icon has only grown in popularity. After being

captured in Africa by the Man in the Yellow Hat and taken to live in the

big city's zoo, Curious George became a symbol of curiosity, adventure,

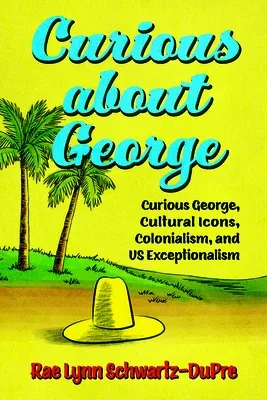

and exploration. In Curious about George: Curious George, Cultural

Icons, Colonialism, and US Exceptionalism, author Rae Lynn

Schwartz-DuPre argues that the beloved character also performs within a

narrative of racism, colonialism, and heroism.

Using theories of colonial and rhetorical studies to explain why

cultural icons like Curious George are able to avoid criticism,

Schwartz-DuPre investigates the ways these characters operate as

capacious figures, embodying and circulating the narratives that

construct them, and effectively argues that discourses about George

provide a rich training ground for children to learn US citizenship and

become innocent supporters of colonial American exceptionalism. By

drawing on postcolonial theory, children's criticisms, science and

technology studies, and nostalgia, Schwartz-DuPre's critical reading

explains the dismissal of the monkey's 1941 abduction from Africa and

enslavement in the US, described in the first book, by illuminating two

powerful roles he currently holds: essential STEM ambassador at a time

when science and technology is central to global competitiveness and as

a World War II refugee who offers a "deficient" version of the Holocaust

while performing model US immigrant. Curious George's twin heroic roles

highlight racist science and an Americanized Holocaust narrative. By

situating George as a representation of enslaved Africans and Holocaust

refugees, Curious about George illuminates the danger of contemporary

zero-sum identity politics, the colonization of marginalized identities,

and racist knowledge production. Importantly, it demonstrates the ways

in which popular culture can be harnessed both to promote colonial

benevolence and to present possibilities for resistance.