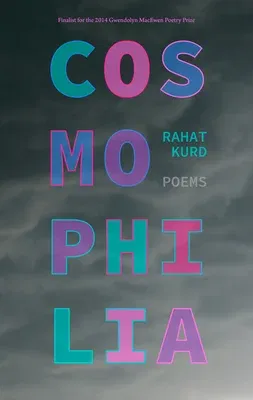

What earthly use is the love of ornament? Slowing down to look closely

at an inherited shawl made by hand, the title poem in Rahat Kurd's

Cosmophilia traces an object of luxury to the traditionally male art

of Kashmiri shawl embroidery. The poet works with images from Kashmir,

her maternal family's place of origin, where the ability to make and

appreciate beautiful things is both absolutely essential and taken for

granted; where increasingly rare levels of artistic mastery are

simultaneously prized and trivialized; where the struggle to carry on

traditional art forms is strained by awareness of increasing

obsolescence, severe political repression, and environmental

degradation; a place both celebrated and dismissed as spectacle, as

"paradise on earth."

The question persists, throughout other poems in Cosmophilia, both as

self-reflexive creative practice and existential dilemma. On the

concrete streets of Vancouver, the anonymity and material ease of cities

tug at the poet's consciousness of frayed traditional ideals, both

philosophical and aesthetic. Religious language and rituals considered

in the aftermath of a marriage take on complex, subversive, and

irreverent layers in a seven-poem sequence. Allusive, playful

multilingual imagery inhabits long narrative meditations, free-form

couplets, and the traditional ghazal, in elegiac or sharply satirical

moods. Nastaliq, a centuries-old form of Persian and Urdu calligraphy,

speaks to the author through the smoke-damaged voice of a fading

celebrity confessional.

The emotionally powerful collection follows the elaborate, unexpected

turns of the poet's imagination, enlisting intricate details of memory

and language and the occasional plain truth - "the hard solitude of the

maker." They intertwine political conflict and family history; they

imagine Hamlet reluctantly confronting the partition of India and

Pakistan. Cosmophilia translates multiple glittering facets of Muslim

culture into, and reflects back from, the immediacy of embodied, urban

Canadian experience.