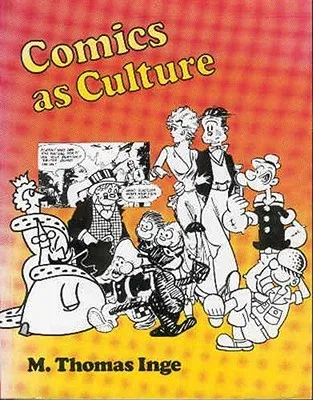

M Thomas Inge

(Author)Comics as CulturePaperback, 1 February 1990

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Print Length

192 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University Press of Mississippi

Date Published

1 Feb 1990

ISBN-10

0878054081

ISBN-13

9780878054084

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

1 February 1990

Dimensions:

27.94 x

20.96 x

1.07 cm

ISBN-10:

0878054081

ISBN-13:

9780878054084

Language:

English

Location:

Jackson

Pages:

192

Publisher:

Weight:

462.66 gm