How Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders exemplified "manhood" and

civic virtue.

Below a Cuban sun so hot it stung their eyes, American troops hunkered

low at the base of Kettle Hill. Spanish bullets zipped overhead, while

enemy artillery shells landed all around them. Driving Spanish forces

from the high ground would mean gaining control of Santiago, Cuba, and,

soon enough, American victory in the Spanish-American War. No one

doubted that enemy fire would claim a heavy toll, but these unusual

citizen-soldiers and their unlikely commander--39-year-old Colonel

Theodore Roosevelt--had volunteered for exactly this kind of mission.

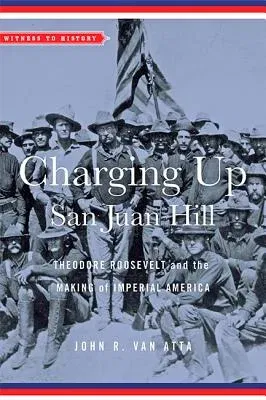

In Charging Up San Juan Hill, John R. Van Atta recounts that fateful

day in 1898. Describing the battle's background and its ramifications

for Roosevelt, both personal and political, Van Atta explains how

Roosevelt's wartime experience prompted him to champion American

involvement in world affairs. Tracking Roosevelt's rise to the

presidency, this book argues that the global expansion of American

influence--indeed, the building of an empire outward from a strengthened

core of shared values at home--connected to the broader question of

cultural sustainability as much as it did to the increasing of trade,

political power, and military might.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Theodore Roosevelt personified

American confidence. A New York City native and recovered asthmatic who

spent his twenties in the wilds of the Dakota Territory, Roosevelt leapt

into the war with Spain with gusto. He organized a band of cavalry

volunteers he called the Rough Riders and, on July 1, 1898, took part in

their charge up a Cuban hill the newspapers called San Juan, launching

him to national prominence. Without San Juan, Van Atta argues,

Roosevelt--whom the papers credited for the victory and lauded as a

paragon of manhood--would never have reached a position to become

president.