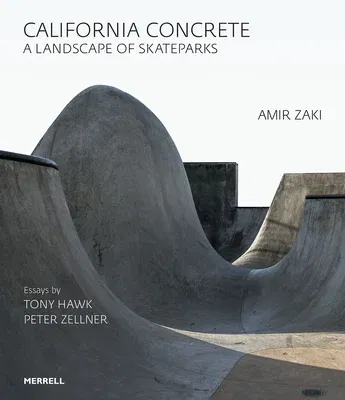

Southern California is the birthplace of skateboard culture and, even

though skateparks may be found worldwide today, it is where these parks

continue to flourish as architects, engineers and skateboarders

collaborate to refine their designs. The artist Amir Zaki grew up

skateboarding, so he has an understanding of these spaces and, as

someone who has spent years photographing the built and natural

landscape of California, he has a deep appreciation of the large

concrete structures not only as sculptural forms, but also as

significant features of the contemporary landscape, belonging to a

tradition of architecture and public art.

To capture the images in this book, Zaki photographed in the

early-morning light, climbing inside the bowls and pipes while there

were no skaters around. Each photograph is a composite of dozens of

shots taken with a digital camera mounted on a motorized tripod head.

The resulting images are incredibly high resolution and can be printed

at a large scale with no loss of detail. Their look is unusual in that

Zaki's lens is somewhat telephoto, which has the effect of flattening

space, yet the angle of view is often quite wide, which exaggerates

spatial depth. The technology also allows Zaki to photograph certain

areas from difficult positions that would otherwise be impossible to

capture. Zaki makes the point that, by climbing deep inside these

spaces, the visual experience is fundamentally different from viewing

them from outside. In his text, Tony Hawk - one of world's best-known

professional skateboarders - describes how Zaki's photographs of empty

skateparks and open skies evoke memories of the idyllic freedom and the

sense of potential that he felt when he first visited a skatepark as a

child and saw skaters flying like birds in and out of the concrete pools

and bowls.

Hawk has skated in some of the parks featured in this book, and for him

several of Zaki's images, taken from the skater's perspective, recall

the experience of trying to learn a particular trick. A beautiful full

pipe that looks like a barrelling wave may be, for Hawk and other

seasoned skateboarders, a perfect example of function and form fitting

together flawlessly in a well-designed skatepark. In his essay, the Los

Angeles-based architect Peter Zellner offers a different perspective.

Skateparks are made by excavating large open areas of land within city

parks. The forms inside them may represent ocean waves, mountainous

terrain and other features from nature, but they are permanently frozen

in cement like Brutalist architecture. Every shape, line, transition,

hip, tombstone, coping, stair, flow, tile, bowl, pipe, spine, rail,

ledge, roll-in, kidney, clover, square and bank serves a specific

purpose - to provide a challenging thrill and maximum pleasure for the

rider. In this sense, skateparks epitomize function over form. In Zaki's

mesmerizing photographs, however, these concrete landscapes suggest a

more complex and integrated relationship with the history of design and

architecture in Southern California.