Nearly sixty years after Freedom Summer, its events--especially the

lynching of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Mickey Schwerner--stand

out as a critical episode of the civil rights movement. The infamous

deaths of these activists dominate not just the history but also the

public memory of the Mississippi Summer Project.

Beginning in the late 1970s, however, movement veterans challenged this

central narrative with the shocking claim that during the search for

Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner, the FBI and other law enforcement

personnel discovered many unidentified Black bodies in Mississippi's

swamps, rivers, and bayous. This claim has evolved in subsequent years

as activists, journalists, filmmakers, and scholars have continued to

repeat it, and the number of supposed Black bodies--never

identified--has grown from five to more than two dozen.

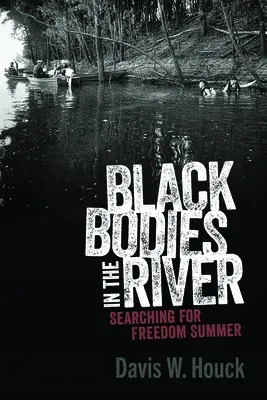

In Black Bodies in the River: Searching for Freedom Summer, author

Davis W. Houck sets out to answer two questions: Were Black bodies

discovered that summer? And why has the shocking claim only grown in the

past several decades--despite evidence to the contrary? In other words,

what rhetorical work does the Black bodies claim do, and with what

audiences?

Houck's story begins in the murky backwaters of the Mississippi River

and the discovery of the bodies of Henry Dee and Charles Moore, murdered

on May 2, 1964, by the Ku Klux Klan. He pivots next to the Council of

Federated Organization's voter registration efforts in Mississippi

leading up to Freedom Summer. He considers the extent to which violence

generally and expectations about interracial violence, in particular,

serve as a critical context for the strategy and rhetoric of the Summer

Project.

Houck then interrogates the unnamed-Black-bodies claim from a historical

and rhetorical perspective, illustrating that the historicity of the

bodies in question is perhaps less the point than the critique of who we

remember from that summer and how we remember them. Houck examines how

different memory texts--filmic, landscape, presidential speech, and

museums--function both to bolster and question the centrality of

murdered white men in the legacy of Freedom Summer.