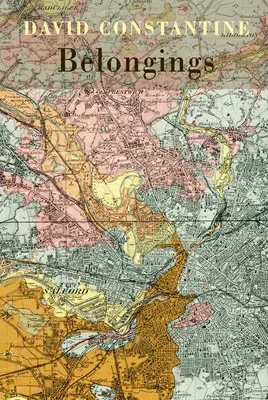

Like the work of the European poets who have nourished him, David

Constantine's poetry is informed by a profoundly humane vision of the

world. The title of his eleventh collection, Belongings, signals that

these are poems concerned both with our possessions and with what

possesses us. Among much else in the word belongings, the poems draw on

a sense of our 'co-ordinates' - something like the eastings and

northings that give a map-reference - how you might triangulate a life.

The poems ask: Where do you belong? And have in mind also the hostile:

You don't belong here. Go back where you belong. Many, possibly all, the

poems in the collection touch more or less closely on such matters.

Perhaps all poetry does, showing a life in its good or bad defining

circumstances. In the poem 'Red', the defining geography is literal,

drawn from an old geological map of Manchester in which Constantine

finds 'the locus itself, a railway cutting / Behind the hospital I was

born in', from which the paths of a life led outward. In other poems the

particular becomes universal, a territory holding all our belongings,

our memories of the people and the places we hold in our hearts. Behind

these explorations another kind of belonging is challenged: our

relationship with the planet to which we belong, but which does not

belong to us.