Selected by Gardens Illustrated for "The Best Gardening Books to Read in

2022"Selected by American Horticultural Society for "Top 10 Books of

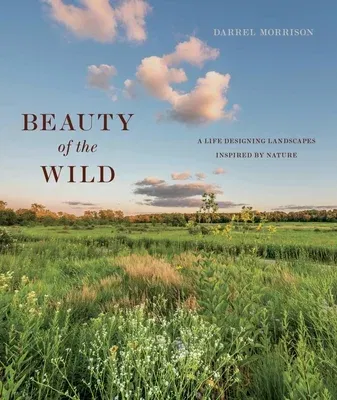

2021"In Beauty of the Wild, Darrel Morrison tells stories of people and

places that have nourished his career as a teacher and a designer of

nature-inspired landscapes. Growing up on a small farm in southwestern

Iowa, Morrison was transported by the subtle beauties of the native

prairie landscape. As a graduate student at University of

Wisconsin-Madison, he encountered the Curtis Prairie, one of the first

places in the world where ecological restoration was practiced. There he

saw the beauty inherent in ecological diversity. At Wisconsin, too,

Morrison was introduced to the land ethic of Aldo Leopold, that we have

a responsibility to perpetuate the richness we have inherited in nature.

He has been guided as well by the teachings of Jens Jensen, who believed

that we can't successfully copy nature, but we can get a theme from it

and use key species to evoke that essential feeling.For more than six

decades, Morrison has drawn inspiration from the varied landscapes of

his life. In native plant gardens at the University of Wisconsin

Arboretum, the New York Botanical Garden, and the Brooklyn Botanic

Garden, he has blended communities of native plants in distillations of

regional prairies, woodlands, bogs, and coastal meadows. At Storm King

Art Center in the Hudson Highlands, his landscapes capture the essence

of upstate New York meadows. These ever-evolving compositions were

designed to reintroduce diversity, natural processes, and naturally

occurring patterns--the "beauty of the wild"--into the landscape. For

Morrison, however, there is also a deeper motivation for designing these

landscapes. Strongly influenced by Aldo Leopold's observation that

people start to appreciate nature initially through its pretty elements,

he explains: "From admiring individual plants within a big composition,

you can move to starting to see patterns, and then this leads to

starting to think about processes that have led to the patterns. It is a

progression. You start to think more about why things are where they

are, and how you can perpetuate that, and even deeper, you really start

to think about protecting, preserving, and restoring these qualities in

the landscapes we are responsible for."