The roots of white supremacy lie in the institution of negro slavery.

From the 15th through the 19th century, white Europeans trafficked in

abducted and enslaved Africans and justified the practice with excuses

that seemed somehow to reconcile the injustice with their professed

Christianity. The United States was neither the first nor the last

nation to abolish slavery, but its proclaimed principles of freedom and

equality were made ironic by the nation's reluctance to extend

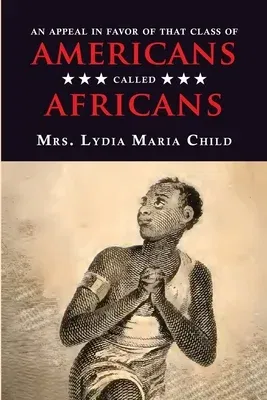

recognition to all Americans. "Americans" is what Mrs. Child calls those

fellow countrymen of African ancestry; citizenship and equality are what

she proposed beyond simple abolition. While Mrs. Child expected the

Appeal to offend and alienate a significant portion of her large

audience, she wrote "it has been strongly impressed upon my mind that it

was a duty to fulfil this task; and earthly considerations should never

stifle the voice of conscience." Thirty years before Abraham Lincoln's

Emanicipation Proclamation, she assembled the evidence for liberation

and placed it before a large national audience. Her work helped push

national emancipation into the mainstream, and her research supplied a

generation of later essayists and pamphleteers with essential background

for the continuing debate on the most vital issue in American history.