Megan Raby

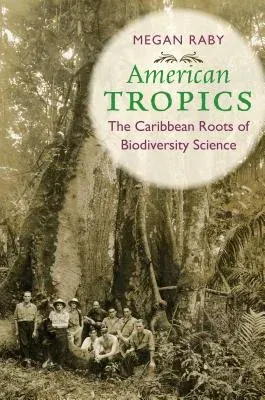

(Author)American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity SciencePaperback, 13 November 2017

Qty

1

Turbo

Ships in 2 - 3 days

In Stock

Free Delivery

Cash on Delivery

15 Days

Free Returns

Secure Checkout

Part of Series

Flows, Migrations, and Exchanges

Print Length

336 pages

Language

English

Publisher

University of North Carolina Press

Date Published

13 Nov 2017

ISBN-10

1469635607

ISBN-13

9781469635606

Description

Product Details

Author:

Book Format:

Paperback

Country of Origin:

US

Date Published:

13 November 2017

Dimensions:

23.11 x

15.49 x

2.79 cm

Genre:

Caribbean

ISBN-10:

1469635607

ISBN-13:

9781469635606

Language:

English

Location:

Chapel Hill

Pages:

336

Publisher:

Weight:

498.95 gm