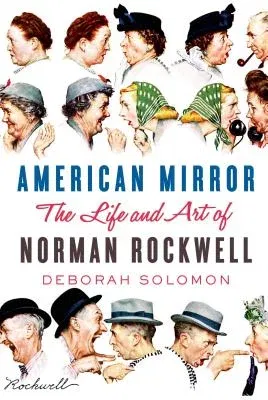

"Welcome to Rockwell Land," writes Deborah Solomon in the introduction

to this spirited and authoritative biography of the painter who provided

twentieth-century America with a defining image of itself. As the star

illustrator of The Saturday Evening Post for nearly half a century,

Norman Rockwell mingled fact and fiction in paintings that reflected the

we-the-people, communitarian ideals of American democracy. Freckled Boy

Scouts and their mutts, sprightly grandmothers, a young man standing up

to speak at a town hall meeting, a little black girl named Ruby Bridges

walking into an all-white school--here was an America whose citizens

seemed to believe in equality and gladness for all.

Who was this man who served as our unofficial "artist in chief" and

bolstered our country's national identity? Behind the folksy,

pipe-smoking facade lay a surprisingly complex figure--a lonely painter

who suffered from depression and was consumed by a sense of inadequacy.

He wound up in treatment with the celebrated psychoanalyst Erik Erikson.

In fact, Rockwell moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts so that he and his

wife could be near Austen Riggs, a leading psychiatric hospital. "What's

interesting is how Rockwell's personal desire for inclusion and normalcy

spoke to the national desire for inclusion and normalcy," writes

Solomon. "His work mirrors his own temperament--his sense of humor, his

fear of depths--and struck Americans as a truer version of themselves

than the sallow, solemn, hard-bitten Puritans they knew from

eighteenth-century portraits."

Deborah Solomon, a biographer and art critic, draws on a wealth of

unpublished letters and documents to explore the relationship between

Rockwell's despairing personality and his genius for reflecting

America's brightest hopes. "The thrill of his work," she writes, "is

that he was able to use a commercial form [that of magazine

illustration] to thrash out his private obsessions." In American

Mirror, Solomon trains her perceptive eye not only on Rockwell and his

art but on the development of visual journalism as it evolved from

illustration in the 1920s to photography in the 1930s to television in

the 1950s. She offers vivid cameos of the many famous Americans whom

Rockwell counted as friends, including President Dwight Eisenhower, the

folk artist Grandma Moses, the rock musician Al Kooper, and the

generation of now-forgotten painters who ushered in the Golden Age of

illustration, especially J. C. Leyendecker, the reclusive legend who

created the Arrow Collar Man.

Although derided by critics in his lifetime as a mere illustrator whose

work could not compete with that of the Abstract Expressionists and

other modern art movements, Rockwell has since attracted a passionate

following in the art world. His faith in the power of storytelling puts

his work in sync with the current art scene. American Mirror

brilliantly explains why he deserves to be remembered as an American

master of the first rank.