Caesar's Legions laid siege to Vercingetorix's Gallic army in one of the

most tactically amazing battles of all time. Outnumbered 6:1, the Romans

built siege lines facing inward and outward and prevented the Gauls from

breaking the siege. The campaign leading to the battle revealed

ingenuity on both sides, though in the end Caesar established his fame

in these actions.

In 52 BC, Caesar's continued strategy of annihilation had engendered a

spirit of desperation, which detonated into a revolt of Gallic tribes

under the leadership of the charismatic, young, Arvernian noble,

Vercingetorix. Though the Gallic people shared a common language and

culture, forging a coalition amongst the fiercely independent tribes was

a virtually impossible feat, and it was a tribute to Vercingetorix's

personality and skill.

Initially Vercingetorix's strategy was to draw the Romans into pitched

battle. Vercingetorix was soundly beaten in the open field battle

against Caesar at Noviodunum, followed by the Roman sack of Avaricum.

However, the action that followed at Gergovia amounted to the most

serious reverse that Caesar faced in the whole of the Gallic War.

Vercingetorix began a canny policy of small war and defensive maneuvers,

which gravely hampered Caesar's movements by cutting off his supplies.

For Caesar it was to be a grim summertime - his whole Gallic enterprise

faced liquidation.

In the event, by brilliant leadership, force of arms, and occasionally

sheer luck, Caesar succeeded. This culminated in the siege of Alesia

(north of Dijon), which Caesar himself brilliantly narrates (Bellum

Gallicum 7.68-89). With his 80,000 warriors and 1,500 horsemen

entrenched atop a mesa at Alesia, the star-crossed Vercingetorix

believed Alesia was unassailable. Commanding less than 50,000

legionaries and assorted auxiliaries, Caesar nevertheless began the

siege. Vercingetorix then dispatched his cavalry to rally reinforcements

from across Gaul, and in turn Caesar constructed a contravallation and

circumvallation, a double wall of fortifications around Alesia facing

toward and away from the oppidum. When the Gallic relief army arrived,

the Romans faced the warriors in Alesia plus an alleged 250,000 warriors

and 8,000 horsemen attacking from without. Caesar adroitly employed his

interior lines, his fortifications, and the greater training and

discipline of his men to offset the Gallic advantage, but after two days

of heavy fighting, his army was pressed to the breaking point. On the

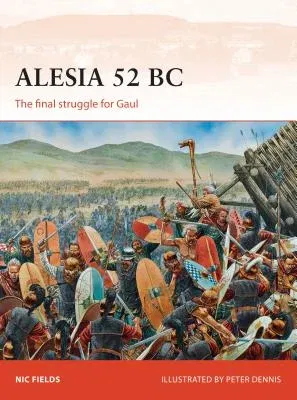

third day, the Gauls, equipped with fascines, scaling ladders and

grappling hooks, captured the northwestern angle of the circumvallation,

which formed a crucial point in the Roman siege works. In desperation,

Caesar personally led the last of his reserves in a do-or-die

counterattack, and when his Germanic horsemen outflanked the Gauls and

took them in the rear, the battle decisively turned. The mighty relief

army was repulsed.

Vercingetorix finally admitted defeat, and the entire force surrendered

the next day. Alesia was to be the last significant resistance to Roman

will in Gaul. It involved virtually every Gallic tribe in a disastrous

defeat, and there were enough captives for each legionary to be awarded

one to sell as a slave. In a very real sense Alesia symbolized the

extinction of Gallic liberty. Rebellions would come and go, but never

again would a Gallic warlord independent of Rome hold sway over the

Celts of Gaul.